Part 1 of a 3 part series on Visiting Kinbiken. I am grateful to Alice Liddell and Desi La for their help with translation during the afternoon.

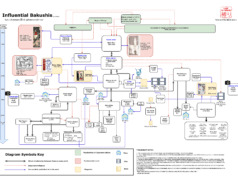

On December 4th, I had the pleasure of visiting Naka Akira’s second meeting of Kinbiken. The group takes it name from a shortened version of 緊縛美研究会, or “Kinbakubi kenkyūkai” which translates to something like “the society for the study of beautiful bondage.” The meeting is a continuation of a series of gatherings started in 1986, led by Nureki Chimuo, Naka sensei’s teacher and mentor.

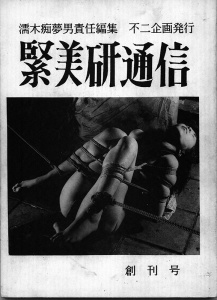

The event would lead to a series of videos and the publication of a magazine, 緊美研通信, Kinbiken Communication.

The event would lead to a series of videos and the publication of a magazine, 緊美研通信, Kinbiken Communication.

Even though Nureki passed away in 2013, his presence was still felt throughout the day. In fact, I would go as far as to say the memory of Nureki was a consistent theme in almost everything Naka sensei discussed.

I have chose to call these articles “Visiting Kinbiken” because so much of what I felt was that in this space I was truly that, a visitor. Just the name itself Kinbiken evokes for me a history and culture that I feel I have only a limited grasp on. Even with expert translators, it was challenging to grasp the subtlety of much of what was said. As such, what I am sharing in these articles is as much an interpretation of events as it is reportage. In many cases, the thoughts and feelings Naka sensei expressed seemed very personal and I was left feeling that in many cases they were things best left to him to share himself.

One thing that was a core part of the experience was both Naka sensei and Kinbiken’s connection to Nureki.

It was clear, as the day progressed, that for Naka sensei, Nureki’s role in the world of kinbaku was about much more than just his tying, it was about how he chose to share that skill and how he helped define and shape the culture of kinbaku that we still participate in today.

A lot of what Naka sensei discussed were specific memories of his teacher, from his general sensibilities to specific details, right down to how Nureki would massage his new rope with his fingers, inch by inch to break it in (rope, Naka explained, was much rougher and hard to work with in those days and required a lot more preparation). He explained that rope was oiled to make it heavier so it made a strong impression when it would hit the tatami mat when you were tying.

In the audience of about 30 people, a handful had been former attendees of Kinbiken in the 1980s, who also shared many memories of the early days of kinbiken during the breaks.

What was most striking to me was Naka sensei’s desire to maintain a link to the past, to the history of kinbaku and to keep alive Nureki’s memory. Nureki, he told the room, was quite famous for “barking” at the rope community. He was a man of very strong opinions and was never shy about sharing them and frequently did, both at kinbiken and later through his blog. It was not clear if it was planned or inspired by the moment, but Naka announced to the room that he felt the need to begin taking on that role. And bark he did.

Between tying three different models for the day (which will be the subject of part 2), Naka sensei elaborated on many themes, but for me, three stood out as being critically important to his way of thinking about kinbaku. His opinions were delivered directly and in some cases harshly. The points I want to emphasize are, I believe, related and speak to a larger question, not only about how we practice kinbaku, but of what, at its core, Naka sensei believes kinbaku is about.

It was well known that Nureki had a strong dislike for rope performance and that sentiment was echoed by Naka sensei. He suggested that performance often presents kinbaku in a context that misses the essential communication between the people engaging in the act. His first tie of the afternoon was a demonstration of that feeling, pushing his model to the edge of what she could manage and repeatedly pulling back and pushing again. Finding those edges, for Naka sensei, was what he described as the essence of kinbaku and was something not possible in performance. Naka went on to say that he will be reducing the number of performances he will do over the next year.

Later in the day, Naka brought up the topic of injury and risk, being somewhat critical of recent discussions of rope injury in the community. Injuries, he explained, are a part of doing kinbaku, especially when you are playing with the edges. When working at a very high level, particularly with semenawa, it is not reasonable to expect that models will always walk away unscathed. He spoke about the various injuries he had caused over the years, including some serious ones with people he knew well and had worked with for many years.

His point was not that we shouldn’t tie safely or that we shouldn’t pay attention to the risks of tying, but that when you are exploring the edges and doing risky things, accidents are much more likely to happen. He described his work with Sugiura sensei as constantly pushing the envelope, always looking for the limits of kinbaku in order to capture the extremes.

The danger, Naka said, was not in the controlled environment that he ties in. Models, as well as bakushi, all know the risks and have decades of experience in creating the scenes that are captured. The risk comes when those without the training and experience see these dramatic poses and attempt to recreate them on their own.

The final concern that Naka sensei expressed was with the popularity and commercialization of kinbaku. The risk he spoke of, as I understood him, was not the accessibility or amount of kinbaku being done, but the effect that the exposure has had on the art itself. Like Nureki, Naka sensei, expressed a strong desire for kinbaku to remain hentai, preserving a feeling of both eroticism and perversion. It is a feeling he has expressed before in different contexts. Staying outside the mainstream is something that he expressed was very important to maintaining the integrity of the art and that integrity comes from the things he discussed throughout: pushing boundaries and creating connection and communication.

The revival of Kinbiken is much more than just a rope event or a venue for sharing kinbaku; it is a kind of memorial. The memory of Nureki sensei was very much alive and being channeled through Naka in his comments and his tying throughout the afternoon.

Even the choice of the name speaks to a deeper issue emerging in kinbaku. As we witness the passing of many of the first generation of rope masters, we find ourselves losing more and more touch with the history of the art. While change and growth are inevitable, forgetting our past creates the risk of losing touch with the deeper parts of what kinbaku is and can mean to those who practice it and see it as a way to share and communicate with their partners.

For Naka sensei, like Nureki before him, kinbiken is a way to share a way of thinking about kinbaku that transcends the question of how we tie and delves into the deeper and more complicated question of why we tie.

I was honored to be able to spend the day with so many others and enjoy a small taste of what that means.